There has always been a fine line between beauty as an enchanting glimpse into the heavenly, and beauty as a self obsessed and devilish vanity. Particularly as a woman, this balance is precarious if not doomed.

Death and the devil attack two women who are looking in a hand-held mirror

David Funck, printed late 1600s,

Germany

The exhibition begins with the usual suspects: a reproduction of the Nefertiti bust, reproductions of reclining Roman sculptures - including the sleeping hermaphrodite (a sensuous mattress later added by Bernini) and moves on to vanitas with the inevitable cartoons mocking such obsessions with attaining worldly beauty. The way the exhibition is set out is quite haphazard and patchy, with some sections absolutely captivating and some leaving you cold.

Overall I really enjoyed it although it didn’t have the most linear direction and it doesn’t speculate as to the future of beauty. It ends with a sombre look at beauty today. Which naturally is: obsessive selfies and a bland state of endless copycat looks on social media. There was an excellent section discussing how mirrors were originally made from copper and then bronze for instance: The ancient Egyptian mirror they had on show, gave a hazy approximation of one’s reflection. It was strange to look into a mirror like that.

Ancient Egyptian bronze mirror

Unknown maker

800-100 BCE, Egypt

To know that in ancient times, your audience and the way people looked at you was your mirror; you would never truly see yourself aside from this blurry image. And this they positioned alongside - well who else? - Kim Kardashian and her ‘ironic’ book of selfies, “Selfish.” They could have then built on this notion of how far we’ve come from near blindness of one’s physicality to this omnipresent ability to take selfies and be filmed every time we emerge, to perhaps wonder what the future will be. Perhaps a time when we can see ourselves in 3D not 2D, perhaps even talk or interact with ourselves to the point that future beings would wonder, how did people in the olden days bear to only know themselves as 2D images? But, nothing is said about future projections. And nothing is said about how beauty is connected to health. Instead the exhibition focuses on attempts to attain beauty via makeup, ointments, fashion, medicine, or tools.

Not that this is not a fascinating angle. The highlights for me were: a section recreating beauty recipes aka “Renaissance goos” from the 1500s (apparently often made by Jewish women immigrants who had been expelled from Spain in 1492.) There was an accompanying video showing the recipes being followed and the resulting creams. I would be tempted to buy a jar!

Ivory mortar and pestle, carved with cherubs, alchemy scenes and a snake

Unknown maker

1501-1700, Europe

Then, a life size Barbie which was both startling and sad. It was so wholly unrealistic and served as ultimate proof that Barbie really always was unattainable beauty which could never occur in real human life.

Lifesize Barbie and Oriol

Adel Rootstein Ltd.

2009, Germany

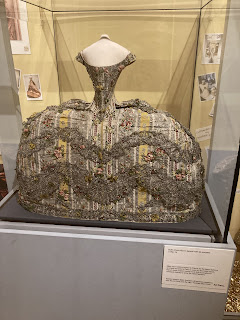

The section on beauty spots and corsets and the accompanying Georgian satirical cartoons were expected but no less amusing for it.

A dandy being laced into a tight corset by two servants

1819, England Thomas Tegg

A young woman greeted by a brothel keeper with prominent beauty patches

A Harlot's Progress series

William Hogarth

1732, England

And the section on trans although not really about beauty anymore, in fact to count in within beauty seemed to trivialise it I thought. But nonetheless quite powerful. A somewhat gory couple of jars hold a breast each. The accompanying plaque quote their original owner, E-J Scott. “In this photo, you can see me holding up a jar of my own chest tissue. In front of the photo, you can see the same artefact. A cis-gaze will inevitably try to piece the body and the person back together. But this optical exercise defies resolution: I have curated my gender with intentionality. My intention is that your inspection does not interrupt my self-reflection.”

This section also had some seemingly innocuous items collected by trans individuals. Handwritten notes about what the objects meant to them and how they had helped them to change their outer body to match their true selves. It was then followed by some modern art installations which made very banal and hackneyed points about how hard it is to be yourself (or whatever a sculpture made out of your mum’s old photos and nighties is meant to conjure up.)

And then some flashing videos of tik tok etc beauty looks all merging into one being with no individuality whatsoever. Well we knew that too and these hardly need their own section.

All in all though I found it very interesting and I liked the commentary on L’Oréal’s master stroke marketing line “Because I’m worth it!” Guilt tripping women into thinking if they don’t buy it then they’re admitting they’re not worth it. Genius. And this line is still used today. That’s sobering.

Men also feature and are also mocked, to a lesser extent. Their position is as the nasty voice abusing and mocking women through the ages. This via cruel cartoons, or cataloguing and awarding women’s beauty rankings.

Hogarth again.Wigs classified in a parody of the orders of ancient Greek and Roman architecture

William Hogarth

1761, England

But, beauty is not just about pleasing others, it is also about the joy of lavishing oneself. And, at times this came across. The ancient Egyptian beauty products in the shape of a turtle, a woman, or a fish, exhibited alongside a 20th Century items such as a British airways compact (lent by Lisa Eldridge of course - who else has such fine trinkets!)

The section on ethnic beauty was promising but too self consciously done. And putting Rihanna’s makeup in there felt a little gratuitous. She is not above straightening her hair and capitulating to society’s expectations. I don’t believe even if her collection has the most shades, that it was the first to welcome dark shades for the masses. It felt as if the last few sections of the exhibition moved away from a joyful celebration of adornment and took a more watchful approach. The shadow of cancel culture loomed at times.

The Book of Fair Women, German photographer E.O. Hoppé 1810

Josephine Baker in banana skirt , 1930s

The final section left the exhibition on a flat note. Plastic surgery epitomised by a harrowing photograph of a young woman being inspected before getting new breasts, and a despondent vision of chasing beauty being something shameful and to be struggled against.

However the fascinating sections were brilliant… so for that reason I would still give this a solid 4/5

The Cult of Beauty 26 October 2023 – 28 April 2024 - Wellcome Collection